Welcome to the latest issue of Bar Italia!

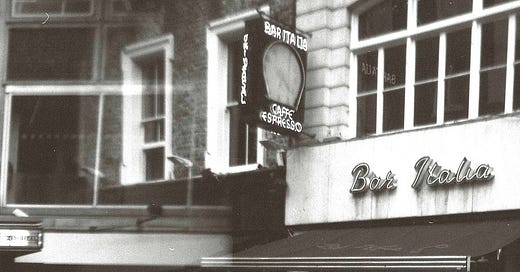

Bar Italia is the newsletter for those interested in Italy and Italian politics but looking for a broader, less detailed overview than The Italian Compass. If you’re curious about why this newsletter is titled “Bar Italia” and how it’s structured, I invite you to read the introduction to the inaugural issue. As anticipated, this is the last issue for a while, and Bar Italia will return in early July.

If you’d like to discuss any of the topics covered in this issue, feel free to reach out via email by clicking here.

Hope you find it interesting!

Dario

Bar Italia - #12

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has declared that Israel is prepared to act independently to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons, stating that this course of action does not hinge on U.S. involvement or decisions by former President Donald Trump. The American President said he would make a decision within two weeks regarding potential military intervention in the escalating conflict. However, a new poll reveals that most of his supporters oppose U.S. military involvement against Iran. Against this backdrop, Italy is closely monitoring developments following the recent G7 summit and the broader geopolitical consequences of a potential U.S.-led offensive. An emerging debate is underway about what Italy should do if the U.S. decides to go to war with Iran. Italian Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani had a conversation with U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio to emphasize the need for a diplomatic resolution to the Israel-Iran standoff. Tajani also underscored the urgency of achieving a ceasefire in Gaza and renewing peace talks between Russia and Ukraine. At the G7 summit, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni emphasized the need for negotiations to prevent Iran from becoming a nuclear power, rejected the idea of Russia mediating in the conflict, and expressed support for a ceasefire in Gaza. She also reiterated that any Italian participation in a conflict with Iran would require formal parliamentary approval.

Italian Defense Minister Guido Crosetto firmly stated that Italy will not take part in any military operations against Iran. He stressed the importance of diplomatic de-escalation and advised Italian citizens currently in Iran to leave the country due to increasing risks. A potential point of contention involves U.S. military bases in Italy. Crosetto clarified that under a decades-old agreement from the 1950s, these bases can only be used with explicit authorization from the Italian government—a request the U.S. has not yet made. However, in the event of an American attack on Iran, it is extremely unlikely that the U.S. would proceed without using its Mediterranean bases. As such, the potential use of these bases in a war with Iran raises strategic concerns. Will Italy join the war? The current situation is reminiscent of 2003, when the U.S. decided to attack Iraq. If Trump goes all in on attacking Iran, it will put Meloni and the Italian government in a very tight spot. On one hand, the importance of the Atlanticist dimension in her foreign policy—and her political connections with the Trump administration—would make it difficult for Meloni to avoid aligning with the U.S. On the other hand, this could put her on a collision course with several EU partners, as well as with a significant portion of Italian public opinion. The so-called E3 countries (France, Germany, and the UK) are trying to mediate, as they are meeting today with Iran’s foreign minister in Geneva. If the U.S. does attack Iran, I believe it will be nearly impossible for the current Italian government to remain on the sidelines without eventually paying a high price in terms of deteriorating relations with the American administration—a price I don’t think Meloni is willing to pay. Personally, I’m skeptical that a full-scale war against Iran makes strategic sense (2003 Iraq should definitely serve as a lesson here), and I don’t think Italy’s direct participation would be beneficial. That said, I don’t work for the Italian government, nor do I advise anyone there—so who cares what I think!

Italy’s recent referendum on labor protections and citizenship reform failed to cross the constitutional threshold—the so-called quorum—required for validation. Despite a clear majority of “Yes” votes across all five questions, the initiative was rendered void due to low voter turnout. Final figures confirmed a turnout of 30.5 percent—well below the 50 percent plus one required by Article 75 of the Constitution. The referendum questions received overwhelming support from those who voted. Measures such as reinstating unjustly dismissed workers, limiting compensation caps on dismissals, and reinforcing protections for fixed-term contracts each garnered over 87 percent approval. Similarly high support was recorded for extending liability in workplace accidents. However, the proposal to reduce the time required to obtain Italian citizenship had comparatively lower backing, with 64.66 percent voting in favor—showing how complex and polarizing this issue remains, even for center-left voters. Maurizio Landini, head of the CGIL union and one of the initiative’s main advocates, acknowledged the outcome as a disappointment. While he refrained from framing it as a complete failure, he admitted that the intended objectives were not met. Nonetheless, he viewed the participation of 14 million voters as a potential foundation for future engagement—even as he pointed to a broader democratic crisis (classic Landini line when he politically loses, which is becoming the norm). When asked about resigning from his leadership role, Landini made it clear he had no such plans (of course—if he had to leave every time he was defeated, his career would’ve ended years ago).

The broader political repercussions are considerable. The referendum’s collapse is widely interpreted as a blow to the left and a reinforcement of Giorgia Meloni’s government. The center-right swiftly labeled the turnout a historic failure. Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani called for a reconsideration of the current referendum legislation. Reactions on the left were mixed and often conflicted. Elly Schlein, secretary of Partito Democratico, underscored the significance of the 14 million votes as a sign of public desire for reform. However, politically, she is the main loser: she critically followed Landini on this, thinking this vote could have been the spallata (push) needed to weaken Meloni. That didn’t happen. Francesco Boccia, Senate leader for the PD, argued that the turnout deserves the same respect as the 12.3 million votes that brought Meloni to power (whatever that means). Riccardo Magi of +Europa went even further, calling for reform of the quorum requirement, noting that the referendum attracted more participation than the last national elections that legitimized the current government (which is not true, by the way, but I’d have to get into the details—and there’s no space here).

If they were my students back when I was a teaching assistant in Political Science at L’Orientale in Naples (2005–2009—those good old days when I was young, full of enthusiasm, and still believed the future had potential... unlike now), I would’ve sent them home for making that kind of comparison in an exam. Comparing elections that are completely different in terms of political meaning, organization, and institutional purpose simply makes no sense. Many people are now wondering: can Giorgia Meloni govern until 2032? Well, it would be a first in Italian politics (after all, not even Berlusconi in his prime managed to stay ten years in a row at Palazzo Chigi). But after this failed referendum, I’d say Meloni’s chances of staying in power until 2032 are higher than they were a month ago. The opposition is in a really—and I really mean really—bad state.

The upcoming NATO summit on June 24–25 in The Hague is set to tackle a divisive proposal: raising defense spending targets to 5% of GDP by 2035. The plan has stirred concerns across member states over its fiscal and political ramifications, particularly as it comes amid heightened tensions and growing military demands. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte has suggested splitting the target—3.5% of GDP dedicated to military expenditures and an additional 1.5% for broader security initiatives—to be implemented over seven years. Italy, however, is urging a longer timeline. Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani has called for a ten-year horizon, expressing optimism that a consensus can still be reached. The Meloni government recently adjusted its defense spending metric from 1.5% to 2.0% of GDP, though this was more the result of fiscal creativity than actual changes in spending patterns. Still, Italy remains well below the proposed targets and is now lobbying to phase in any increase more gradually. This debate unfolds just as European allies prepare to face former U.S. President Donald Trump at the summit—a figure likely to press hard on defense commitments. For Rome, this issue is extremely delicate. Meanwhile, FlightGlobal International has placed Italy 14th globally in air power, marking a drop from its previous top-ten standing—one more piece of evidence, if any were needed, that Italy has a real problem with military readiness.

As NATO leaders prepare to meet, M5S leader Giuseppe Conte is organizing a parallel gathering in The Hague, aiming to unite European parties against the growing tide of military spending. The former prime minister is calling for a grassroots movement to resist the continent’s rearmament, advocating for a Europe that chooses diplomacy over escalation. The M5S is going full-on pacifist. Together with members of Alleanza Verdi Sinistra (The Left), M5S parliamentarians declined an invitation from Defense Minister Crosetto to an informal lunch he offered to discuss national security and military responsibilities with members of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly delegation. Crosetto, whose temperament is well known, was visibly irritated, criticizing their absence and labeling it disrespectful to institutions, while emphasizing the importance of dialogue on national security issues. However, if I may speak from experience—for M5S parliamentarians to skip an institutional lunch, it must have been a really big deal. They’re usually quite keen on attending these events. Dario Carotenuto, an M5S deputy who has recently gained attention on social media for his anti-Israeli positions, has openly criticized Italy’s NATO membership, claiming it reduces the country to a position of subservience, stating he would love to see Italy leaving NATO. Carotenuto was elected in the Naples district that includes Secondigliano—the very neighborhood where I was born and raised. Each time I return and talk to locals, I make a point of asking whether they know him. The answer, more often than not, is a puzzled “Who?” His name does not resonate even in the streets he’s meant to represent. Which, I think, is quite telling. It speaks both to the M5S’s limited presence on the ground and to how the movement is increasingly defining itself: focused on broad, ideological battles, with very little engagement on more local or pragmatic issues. Carotenuto’s radical rhetoric aligns with the movement’s broader anti-militarist stance, which is becoming more and more pronounced these days. Why? I think M5S—especially Conte—smells Schlein’s weakness, even more so after the referendum. This is an extremely important dynamic to monitor: Schlein was chosen as PD secretary to drain M5S votes. If the opposite starts to happen, the PD might be in real trouble. More broadly, if the center-left coalition is perceived as leaning too far left, there might be an additional exodus of centrist voters—either to the small centrist parties on the fringes of the coalition (Renzi, Calenda, etc.) or to Forza Italia. Either way, this spells trouble for the PD.

In an interesting article published a few days ago, Defense News voice the concerns regarding the future of the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), the sixth-generation fighter jet development initiative jointly led by the United Kingdom, Italy, and Japan). President Trump has allegedly proposed the sale of the future F-47 fighter jet to Japan. If true, this move could undermine GCAP by potentially prompting Japan to withdraw from the collaboration. According to Italian Air Force General Giandomenico Taricco—now one of the two commercial and corporate directors at the GCAP International Government Organisation (GIGO)—GCAP does not aim to compete with the newly announced U.S. F-47. Instead, the goal is interoperability: two aircraft, one integrated allied system. Taricco emphasized that the F-47 will remain a U.S.-led platform, while GCAP—still targeting a 2035 debut—retains its distinct multinational character. The F-47, announced in March, may take to the skies earlier, but co-ownership of GCAP technology remains a key motivation for Japan for moving ahead with this project. Still, Tokyo’s patience is wearing thin. Amid rising regional tensions and China’s development of its sixth-gen J-50, Japan is reportedly considering a stopgap purchase of additional F-35s. Reuters recently reported concerns about whether GCAP will stay on track for its planned timeline. If GCAP fails, it would be a strategic disaster for Italy.

As analyzed in the latest Italian Compass, Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani is usually seen as ordinary, uncharismatic, and politically cautious. However, this time he appears to have successfully imposed his will on his coalition partners. In recent days, he had theoretically signaled openness to a third term for regional governors—but only in exchange for the adoption of Ius Scholae, a citizenship reform long supported by Forza Italia. Especially after the referendum on citizenship, this was a non-starter for la Lega. Tajani has now come out strongly against proposals to lift the two-term limit for regional presidents, arguing that such a move risks entrenching political power in ways that threaten democratic balance. He reiterated that this reform was not part of the coalition’s electoral platform and warned against using institutional changes as bargaining chips in political negotiations. As a longtime observer of Italian politics, Marcello Sorgi, noted, this effectively amounts to a “Requiem” (end/death) for the third mandate. The consequences will be significant for both coalitions, as prominent figures like Luca Zaia in Veneto and Vincenzo De Luca in Campania will no longer be eligible to run and will force parties to move faster to find suitable options.

Israeli cybersecurity company Paragon Solutions has terminated its contracts with the Italian government following a dispute over the use of its Graphite spyware. The company claims it offered a technical method to verify whether the spyware had been used against Francesco Cancellato, director of Fanpage.it, but Italian authorities declined, citing concerns over classified intelligence and reputational risks. In response, Paragon withdrew entirely from its Italian engagements.

The parliamentary intelligence committee, Copasir, expressed surprise at Paragon’s public remarks and is considering declassifying the transcript of its hearing with the company to ensure transparency. The scandal has since widened: new reports suggest the spyware targeted not only Fanpage journalists but also Dagospia editor Roberto D’Agostino, allegedly surveilled for five months. The Rome Prosecutor’s Office is now conducting forensic analyses on D’Agostino’s phone and those of six others, expanding the legal inquiry and further implicating Italy’s intelligence services (who would have said D’Agostino would have become such an important personality for Italy thirty years ago when he slapped Vittorio Sgarbi live on TV on Italia 1).

In a statement to Haaretz, Paragon said the termination was due to “suspicions of misuse that went beyond the terms of the contract,” adding that questions about journalist surveillance should be addressed to the Italian government. Italy’s journalist organizations, Odg and Fnsi, have voiced strong support for the investigation, demanding answers on how many journalists were affected, who authorized the surveillance, and why. The case has international implications. Dutch journalist and commentator Eva Vlaardingerbroek, whose phone is also under investigation, noted the scandal surfaced in Italy because she resides there and filed a complaint. She stressed that spyware misuse is a broader global issue, affecting journalists and activists across political lines—many of whom received similar alerts from Apple. Among those also under scrutiny are Mediterranea activists involved in migrant rescues, including Luca Casarini, Giuseppe Caccia, and Father Mattia Ferrari. The investigation continues to grow, revealing a complex web of journalism, surveillance, and cybersecurity ethics.

LaVoce.Info analyzed how, over the past two years, high inflation has sharply exposed the impact of fiscal drag in Italy, adding €25 billion in extra tax burdens for employees and pensioners between 2022 and 2024. While this windfall has bolstered state coffers, it has left salaried workers—especially public employees—bearing the brunt. By contrast, self-employed individuals, protected by the flat tax regime, have remained largely unaffected. This is a significant and revealing dynamic—one that could have political consequences for Giorgia Meloni, particularly in regions like Lazio, where public employees have strongly supported Fratelli d’Italia in recent years. If the current fiscal drag mechanism remains unchanged, this could become a sizable electoral bloc willing to shift its support elsewhere. While the PD and other opposition parties have not been particularly aggressive on the issue, it represents a vulnerability that could quietly erode Meloni’s electoral strength if left unaddressed.

The Italian government is fast-tracking a constitutional overhaul of the justice system, with the separation of judicial and prosecutorial careers as its most significant element. The goal is to secure Senate approval by June 26, 2025, paving the way for a national referendum by June 2026. The Partito Democratico has voiced strong opposition, raising concerns about both the substance and the speed of the proposed changes. Interestingly, however, Goffredo Bettini—the historical, left-leaning éminence grise of the PD, speaking from his buen retiro in Thailand—publicly criticized the party’s stance. He argued that the separation of careers is not merely an ideological issue but a necessary step toward equity and a better understanding of the limits of institutional power. It’s no coincidence that his remarks were widely covered by right-leaning newspapers. The opposition’s strategy on this issue could serve as a useful litmus test. If they focus more on judicial reform than on economic and fiscal concerns, it will suggest they are out of touch with Italians’ current priorities—and are unlikely to peel away electoral support from the government.

The European Commission has approved UniCredit’s restructuring plan for Banco BPM, which includes the sale of 209 branches. However, it has rejected Italy’s request to transfer oversight of the operation to the national antitrust authority, maintaining EU jurisdiction over the matter, an outcome the Italian government does not appreciate.

See also…

Politica Estera - The Italian Compass - #8/2025

Politica Estera - Bar Italia - #11/2025

Politica Estera - Scriptorium Italiae #2/2025