The Race for Villa Firenze: Who Will Be Italy’s Next Ambassador to D.C.?

The Context, The Logic, and the Power Dynamics Behind Italy's Most Coveted Diplomatic Post

Introduction

Villa Firenze, in the heart of Rock Creek Park in Washington D.C., is a magnificent place. Since 1977, it has been the Official Residence of the Italian Ambassador to the United States, inaugurated in July of that year by then Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti, and it is one of the most prestigious diplomatic residences in the entire Washington D.C. But beyond the aesthetic beauty of the place, it is also a symbol of the most coveted position in Italian diplomacy: under normal circumstances, it is the “ultimate” diplomatic posting, an almost obvious ambition for anyone who passes Italy’s rigorous entrance exam for diplomatic service.

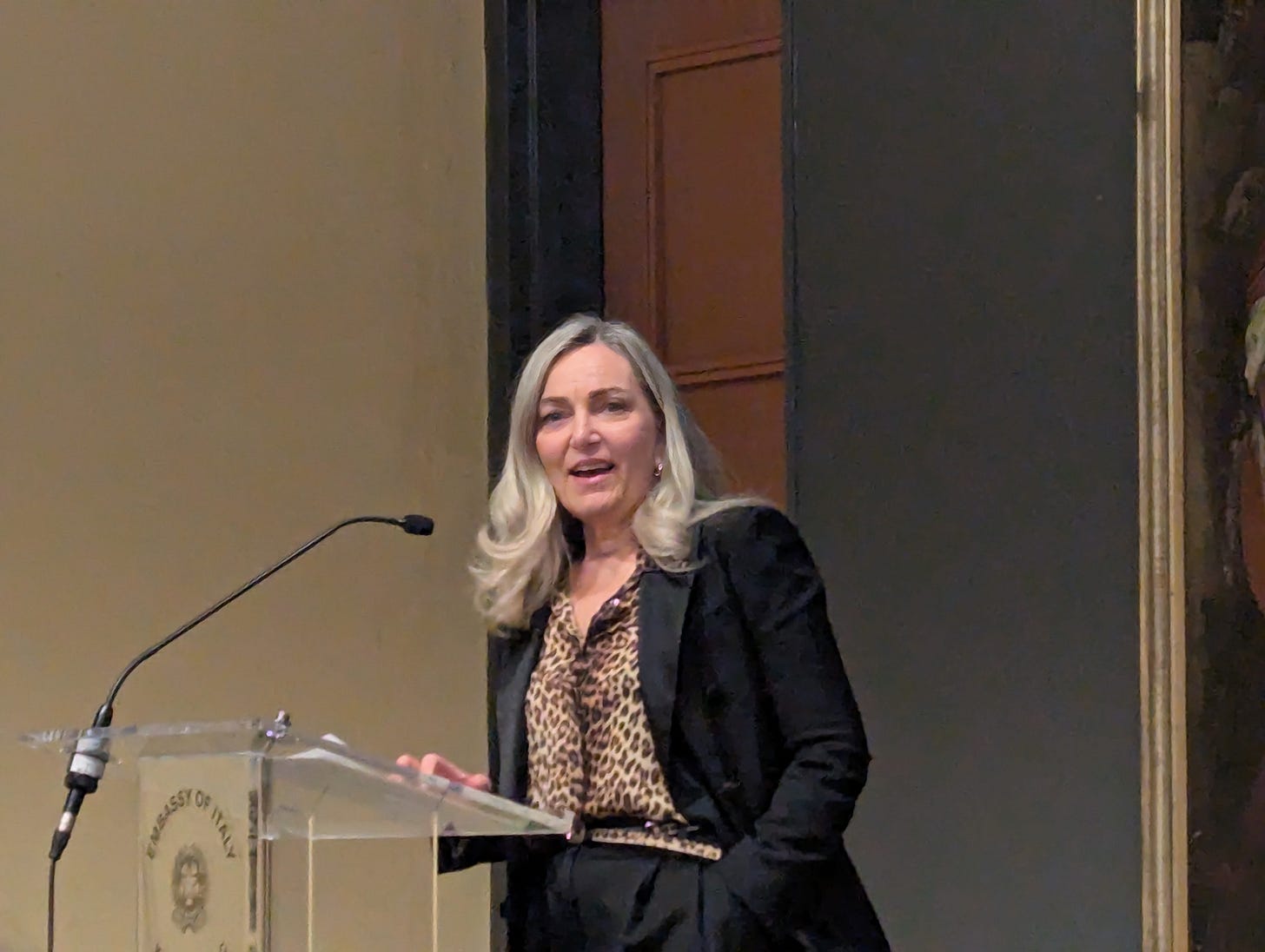

Probably, in terms of impact—on policy, history, and bilateral relations—over the next four years, this post will be even more important than usual. Next June, the current resident of Villa Firenze, Ambassador Mariangela Zappia, the first woman appointed to this position, will leave her post after receiving a one-year extension last year.

For observers of Italian politics, understanding who the next ambassador to D.C. will be is both a divertissement and a necessity: the chosen name, who will be the operational cornerstone of the bilateral relationship, will say a lot about who truly holds power in Rome and how the relationship with Donald Trump’s America will take shape in the coming years.

Will the appointment reflect an identity-driven choice? A negotiated compromise among the all institutions involved? Will the nominee be a politically neutral yet technically accomplished diplomat? A seasoned Ambassador, or perhaps a Minister Plenipotentiary poised—though I remain skeptical—to ascend, while in D.C., into the exclusive Olympus of the Ambasciatori di Grado (Full Ambassadors)?

This first Deep Dive from Politica Estera seeks to unpack these questions. The aim: to provide useful insights for all those who engage daily with Italy’s foreign policy and diplomatic machinery.

The Methodology

A few clarifications on the logic and criteria I used to select potential names:

The next Ambassador must already hold the rank of Ambasciatore di Grado (Full Ambassador — a maximum of 25 in service). In other words, the candidate cannot be a Ministro Plenipotenziario who would be promoted to Ambasciatore di Grado only after being chosen for the post in Washington.

They should not be too close to retirement — ideally, not within one or two years. They also should not have had two consecutive assignments abroad (though I’m not sure how much this actually matters in a case like this).

This is a politically sensitive and high-profile position. It is the most important Embassy in the Italian diplomatic system. The candidate must be someone who strikes the best possible balance between — and can manage pressure from — Il Quirinale, Palazzo Chigi, and La Farnesina, both politically and personally. Formally, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, thus La Farnesina, has the final say, but it’s obvious that Palazzo Chigi will inevitably play a major role in the decision.

This analysis is entirely based on open sources. I should do like top and cool analysts — or the ones who think/pretend to be — who love to brag (often exaggerating) about their “access” to diplomats, policymakers, political leaders; you name it. I’m not that cool, and definitely do not have much access. And yes, I probably shouldn’t admit that so openly — but honestly, I couldn’t care less.

In fact, I might be the only Italian think tanker in D.C. who doesn’t even get invited to the Republic Day reception on June 2. I can’t even remember the last time I spoke to someone at the Embassy — unless renewing my ID card counts. Plus, I’ll be leaving D.C. after the summer, so I won’t even be around when the new ambassador arrives. This means that this piece can be summarized as “no gossip; just analysis, with no agenda.”

Can the “Calenda Precedent” Represent an Option?

These parameters can help narrow down the list of potential candidates, but they shouldn’t be seen as rigid rules. In the end, this is a political decision. If the political leadership wants to appoint someone who doesn’t meet some — or any — of the criteria, it will simply do so.

Let’s not forget: Ambassador Zappia is already, formally, retired. Her extension until June 2025 technically counts as an “external” appointment. A tailor-made decree was required to keep her in place. This is exactly the same procedure Matteo Renzi used in 2016 to appoint Carlo Calenda as head of the Italian mission to the EU in Brussels — a move that caused considerable backlash at the MFA. And not just among senior ambassadors: even junior diplomats protested, publishing an open letter to the then–Prime Minister. Their concern? That this would become the new normal. Who knows what would’ve happened had the 2016 referendum disaster not forced Renzi out of office — rottamandolo — triggering his political downfall?

At the time, Renzi justified the Calenda appointment by saying that diplomats were too soft, and that he needed someone ready to fight in that specific position. Looking back almost ten years later, given how his relationship with Calenda evolved, that statement now feels ironical.

So what if Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni decides the current geopolitical moment — and the stakes of dealing with Trump — require a political appointee? Someone close to her, who responds directly to her, and not a career diplomat?

What if she chooses and imposes a partisan, right-wing intellectual? Marco Tarchi, perhaps — as a way to finally mend ties and heal the historic rift within the Italian Right, dating back to when Giorgio Almirante chose Gianfranco Fini instead of Tarchi to lead the Fronte della Gioventù, sparking the schism that led to the current configuration of the Italian right? Or Marcello Veneziani, in a kind of Pavlovian reflex — a callback to the good old Berlusconi’s days when his name was floated basically for every open position in Italy? To be fair to him, Veneziani himself has never been too interested in many of these positions, just — for a specific period — he was the only well-known conservative intellectual in Italy. Or even Pietrangelo Buttafuoco — aka Giafar al-Siqilli after his conversion to Islam — who would also be Italy’s first Islamic ambassador to D.C.?

Of course, I’m not being serious here. A political appointment is technically possible, but extremely unlikely. It would cause an uproar — and I don’t even want to imagine the mood inside La Farnesina the morning after something like that happens (but I would love to hide somewhere to hear what diplomats would say in such a situation).

But the point is still, theoretically, worth making: this government has a somewhat tense relationship with the Italian bureaucracy in general (what some in the current governmental coalition call, similarly to the U.S., the “Deep State”, lo Stato Profondo). This tension was evident in the recent changes in the intelligence services. Similar undercurrents exist within the MFA apparatus. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone in Meloni’s circle, at some point, floated the idea of a political appointee. That said, it’s not happening.

The Complicated Relationship of Meloni’s Government with Diplomats

The relationship between this government and the MFA bureaucratic structure is, to say the least, complicated. Many top-level diplomats have experienced friction with the current leadership.

Ambassador Luca Ferrari, Italy’s first G7 Sherpa and now Ambassador to Israel, left his position in March 2024. His replacement, Ambassador Elisabetta Belloni — at the time head of Director of the Department of Information for Security (DIS), but first and foremost a top diplomat, former MFA Secretary General — also stepped away, resigning from DIS at the beginning of 2025, moving into a kind of “golden exile” in Brussels as an IDEA diplomatic advisor to the President of the European Commission, Ursula Von der Leyen. Both were said to have had tense relations with Meloni herself.

Francesco Maria Talò, the newly appointed IMEC special envoy, had served as Meloni’s diplomatic adviser — a role increasingly seen in Italy as equivalent to a “National Security Advisor” in the U.S. system. Talò resigned following an incident involving a prank phone call — which was, in reality, an act of hybrid warfare — made to Prime Minister Meloni on September 18, 2023. Russian comedians Vovan & Lexus managed to pose as the head of the African Union and obtained a recorded conversation with the Prime Minister, bypassing normal security protocols for official communications. The event triggered significant criticism of Meloni and her diplomatic staff. Meloni herself stated that she believed “there was a lack of thoroughness by the diplomatic office in properly verifying” the call. Talò resigned as a result.

However, despite this incident, Talò’s relationship with the current government clearly remains positive — as evidenced by his IMEC appointment. It’s worth noting that all three of these ambassadors — Ferrari, Belloni, and Talò — were, at various points (Talò even in recent weeks), rumored candidates for the role of Italian Ambassador to the United States.

If the relationship between the Italian diplomatic machine and Palazzo Chigi is uneasy, the dynamic between the Minister of Foreign Affairs himself, Antonio Tajani, and the structure is also relatively tense. Tajani has reinstated a “politics-first” approach within the Ministry, with him and his team managing everything directly in a top-down fashion — from policy decisions to administrative matters.

Tajani also blocked an initiative by some of Italy’s top diplomats to push through a reform that would raise the mandatory retirement age for ambassadors to 67 — a decision that caused significant friction. The clash involved Tajani’s inner circle, most notably the MFA Secretary General, Amb. Riccardo Guariglia, and many senior diplomats. According to the daily Il Foglio, which is typically well-informed on MFA internal affairs, Giorgio Starace — then Italy’s ambassador to Russia — described the current retirement rule as “discriminatory” in a letter sent to Guariglia and later published by Dagospia (available in its entirety here). Starace even sought support from MPs, particularly inside the League (Lega), to promote a legislative change.

This unusual lobbying did not go unnoticed by Stefania Craxi (yes, the daughter of Bettino Craxi, if you are wondering), Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee — the intended vehicle for the proposed reform. Craxi, who is also a member of Forza Italia (Tajani’s party), immediately informed the Minister, who, according to witnesses, responded badly and rejected any such interferences.

Tajani’s approach marked a sharp U-turn from that of his predecessor, Luigi Di Maio. During Di Maio’s tenure, the bureaucratic apparatus had the upper hand in shaping policy, and diplomats broadly supported him for being someone who “listened to them.” It also contrasts with the brief leadership of Enzo Moavero Milanesi during the populist “yellow-green” government (2018–2019). Moavero, often described as a technocrat, was said to have had a notoriously poor relationship with the diplomatic corps — and minimal influence over policy decisions.

The Names in the Race

So, let’s take a look at which diplomats are actually in the running (at least, based on what is available publicly). Given everything discussed above, the pool of potential candidates is particularly narrow. Because of the importance of the post, many names that have surfaced have already been “burnt”—some, in fact, were likely floated just to be burnt.

As recently as a few days ago, some still floated Talò as a potential choice, despite his recent retirement—but, as noted in the first issue of the Italian Compass, I remained fairly confident he was being lined up for the IMEC role. Amb. Fabrizio Bucci, the former Ambassador to Albania and considered very close to Meloni, was also a name often made, before he was appointed to replace Amb. Armando Varricchio in Berlin.

Given the criteria laid out above and a contextual read of the ministry’s internal dynamics, I believe no more than six names can realistically be considered. Of course, other names could still come up—I think, just to mention a very few, for instance to Amb. Luca Sabbatucci, Amb. Emanuela D’Alessandro, Amb. Bruno Archi, or Min. Marco Peronaci—but here’s my shortlist, in order of likelihood:

Mario Andrea Vattani

Francesco Genuardi

Fabio Cassese

Riccardo Guariglia

Massimo Ambrosetti

Giorgio Marrapodi

Mario Andrea Vattani

Born in 1966, Vattani is both a figlio d’arte, he is the son of Umberto Vattani, twice MFA Secretary General, and a controversial figure in Italian diplomacy. He is currently the Commissioner General for Italy at Expo 2025 Osaka. Minister Tajani is expected to be in Japan with him in the coming days to inaugurate the Italian Pavilion at Expo 2025.

Widely respected—even by his political adversaries—as one of Italy’s top experts on Japan and Asia (as reflected in his books published by Mondadori and Giunti), he is also known for his unabashed right-wing leanings.

He served as diplomatic advisor to Gianni Alemanno during Alemanno’s tenure as Minister of Agriculture and later as Mayor of Rome. Alemanno was the leading figure of the so-called “Social Right” (Destra Sociale) within Alleanza Nazionale, basically the most extreme faction inside the party. In 2012, Vattani also ran for office with La Destra, the party founded by Francesco Storace—Alemanno’s long-time political ally in Alleanza Nazionale. These roles paint a clear picture of his political alignment.

Vattani became a public controversy after performing with his rock band, SottoFasciaSemplice, at an event organized by the neo-fascist group CasaPound. He was accused of giving a fascist salute from the stage. In his defense, he denied doing so on that occasion, though he added, “I wouldn’t claim I’ve never done it in my life either.” Since then, he has been dubbed the “fasciorock consul.”

In 2021, under Prime Minister Mario Draghi, Vattani was appointed Ambassador to Singapore—an appointment that sparked criticism from the Partito Democratico and other left-wing parties in Parliament. However, Marina Sereni, then MFA undersecretary and a member of the PD, publicly stated that Vattani’s work as coordinator for EU–Asia-Pacific relations at the Directorate-General for Globalization and Global Issues had been evaluated as excellent and this was the reason why he was chosen for the Singapore post.

In January 2024, Vattani was promoted to Ambasciatore di grado. According to La Stampa, the promotion was strongly backed by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, allegedly influenced by her undersecretary, Giovanbattista Fazzolari. While few doubt Vattani’s competence—especially his deep knowledge of the Indo-Pacific region, an area of growing strategic interest for the current government—some argue the promotion was driven more by political loyalty than merit. That said, and to be fair to Vattani, such dynamics are hardly unique in Italy’s diplomatic system.

Vattani began his foreign service career in the United States. Given his age, profile, and track record, he is an obvious candidate—actually, the frontrunner—for the D.C. post. Still, some factors may work against his appointment.

One is political: his controversial past would make his posting to D.C. a likely target for opposition attacks. Then again, this could be seen as a strength by some within the ruling coalition—a bold, identity-driven appointment designed to energize the government’s right-wing base and signal a broader ambition to place more ideologically aligned figures in top bureaucratic roles.

Another factor may be personal: Vattani’s deep interest in Japan makes him a strong contender for the Tokyo ambassadorship as well. The current ambassador, Amb. Gianluigi Benedetti, turns 66 on May 1, 2025, and has served in Tokyo since 2021, so he is also close to retirement. Given this context, it wouldn’t be surprising if Vattani himself prefers the Japan posting over Washington. Still, as of now, I think he remains the leading contender, and likely Meloni’s preferred choice.

Francesco Genuardi

Ambassador Francesco Genuardi was appointed Chief of Staff to Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Tajani in 2022. Before that, he served as Italy’s Ambassador to Belgium and the Consul General in New York from 2016 to 2021— so he has already had a U.S. experience during Donald Trump’s first term. Genuardi has long been considered Tajani’s preferred candidate for the D.C. post and is also reportedly favored within the structure of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Last summer, he was widely seen as the frontrunner. However, the landscape has shifted in recent months.

Fabio Cassese

Given the importance of the D.C. post, it’s clear that the Presidency of the Republic will also weigh in. That’s why Ambassador Fabio Cassese’s name has gained traction in recent months. Cassese became the diplomatic advisor to President Sergio Mattarella in late 2022, succeeding Emanuela D’Alessandro, who was appointed Ambassador to France. From 2018 to 2022, Cassese served as Italy’s Ambassador to Jordan. Upon returning to Rome, he took on the role of Director General for Development Cooperation, before moving to the Presidency of the Republic.

These three—Vattani, Genuardi, and Cassese—currently represent the top contenders for the post.

As for the others, another potential candidate, like Genuardi closely tied to the bureaucratic machinery of la Farnesina, is the current MFA Secretary General, Amb. Riccardo Guariglia. Appointed in early 2023 to succeed Ambassador Ettore Francesco Sequi, Guariglia is a highly experienced diplomat. However, it’s unclear how many years remain before his retirement, which could be a limiting factor. Amb. Giorgio Marrapodi, currently serving as Ambassador to Türkiye, is another name that has surfaced frequently. He too may be constrained by age—his mandate in Ankara is ending soon, and retirement is likely approaching. Il Foglio recently reported that Min. Marco Peronaci, Italy’s current representative to NATO, is also among those being discussed. However, Peronaci has not yet attained the rank of full Ambassador (though I’d personally bet he will in the next round of appointments), which could place him at a disadvantage for such a high-profile post—although a move from NATO to Washington, D.C. might not be such a dramatic leap.

Against this backdrop, there is one name that hasn’t been publicly floated for this position—but arguably should be, at least in my opinion: Amb. Massimo Ambrosetti, Italy’s current Ambassador to China. Given the present geopolitical climate, his profile might be particularly well-suited for the position in D.C. In fact, someone with deep insight into China’s strategic thinking – Ambrosetti is a Cambridge-educated China expert – may prove paradoxically more valuable in D.C. than in Beijing, especially in this second Trump presidency which will be defined by the relationship with China (as clearly shown in these early weeks). Understanding how Beijing might respond to U.S. policy shifts could be critical in the coming years.

Ambrosetti brings a distinctive intellectual profile. He has served at the Agency for Cybersecurity, giving him a solid grasp of hybrid warfare and cyber threats; he was previously Ambassador to Panama—a country that is obviously increasingly central to American foreign policy—and also has prior experience in Washington. Although he only began his post in Beijing in 2023 and is not close to retirement, curtailing his term in China remains a possibility.

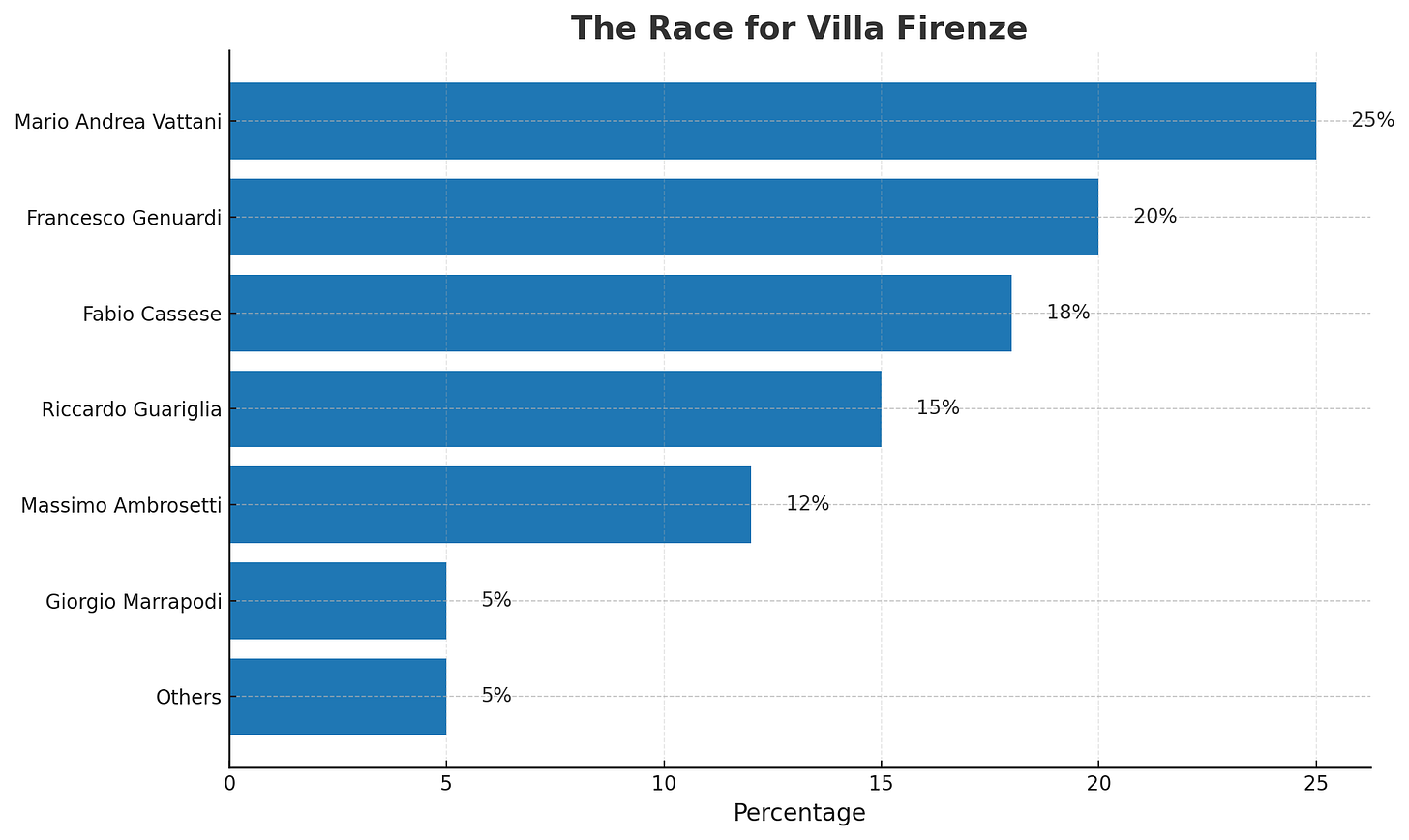

In conclusion, based on the analysis made above, I think the following percentages reflect the estimated chances of each candidate:

Conclusions

Let’s clear the field of any possible misunderstandings: here we’re talking about the very top of Italian diplomacy, so whatever the final decision may be, we are referring to a woman or a man (most likely a man in this case, though again, we cannot be sure) who represents the crème de la crème of one of the most important and selective bureaucracies in the country.

It’s like discussing and analyzing top players from Serie A or the NBA: they are the best of the best, and so all the names mentioned here are of the highest caliber and will do well if selected.

What differs is the political logic behind the choice, and the selected name will serve as an indicator of the current balance of power in Rome; of the reasoning with which the government wants to shape its relationship with an administration like the current American one which—in any case—will be an administration that will leave its mark; and of the future of what remains the most important bilateral relationship in the landscape of Italian foreign policy.

Will it be a candidate with a strong political characterization, competent but controversial, like Vattani? Will it be a name that reflects the establishment, like Genuardi or Guariglia? Or a compromise name agreed upon with the Quirinale, like that of Cassese? Or perhaps an outsider: I suggested Ambrosetti, an extremely competent and eclectic diplomat who - in my opinion - would represent a perfect fit in the current geopolitical context, but there are potentially many others.

You, the readers—who would you bet on?

If you have other names in mind, feel free either to share them in the comments or drop me a line via email. As usual, I can be reached via email at info@politicaestera.net.

Thanks for reading.

See also…

Politica Estera - Bar Italia - #3/2025

Politica Estera - The Italian Compass - #6/2025

Mediterraneo Globale - La Settimana Mediterranea - 9/2025

Politica Estera - Scriptorium Italiae #1/2025